As we approach the end of the VDL commission mandate, now feels like the appropriate time to review just how much the EU regulatory landscape has changed in the last four years and how these new rules will materialise as they come into effect.

To set the scene, here is a quick reminder of the size of the problem we are all dealing with: In 2020, according to figures quoted by ENISA, the cost of cybercrime to the global economy was €5.5 trillion. Also in 2020 a first NIST estimate for the cost of cybercrime to the US economy placed it in the range of 1% to 4% of its GDP. For 2024, most estimates hover around 10 trillion USD or approximately 10% of global GDP. Compare this to the size of the Cybersecurity market estimated somewhere around half a billion. All these figures are very broad estimates because – problem number one – we lack an agreed-upon definition for cybercrime. The latest attempt at a UN Treaty on Cybercrime appears to be stalling on this very point.

Yet most of us, personally or professionally, have already experienced cybercrime first hand. Several recent global surveys reported that 60% or more of organisations surveyed had experienced one or more cyber-attack in the year prior but only half those had reported the cyber-incident to the relevant authority.

We rely on surveys because – problem number two – we lack a comprehensive collection of cyber-incident data -Besides the continued reluctance of organizations to share information on cyber-incidents, structuring the data reported (a taxonomy) to make it exploitable is still work-in-progress.

To complete the picture let’s mention – problem number three– what the WEF, in its Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2024calls a “glaring imbalance of responsibility for security between technology producers and technology consumers” noting that “For years, organizations and individuals have had the primary responsibility for ensuring the hardware and software they use is securely and resiliently implemented, operated and maintained. When incidents do happen, the burden of remediating and recovering from it similarly resides with the user, along with the associated financial burden.” As this picture makes obvious, piecemeal solutions are no longer enough.

As many conclude, cybersecurity needs to evolve to a cooperative effort at – insurable – risk management, extending to the supply chain. To achieve this, we need the enabling legal framework and the data to feed the knowledge base and risk models.

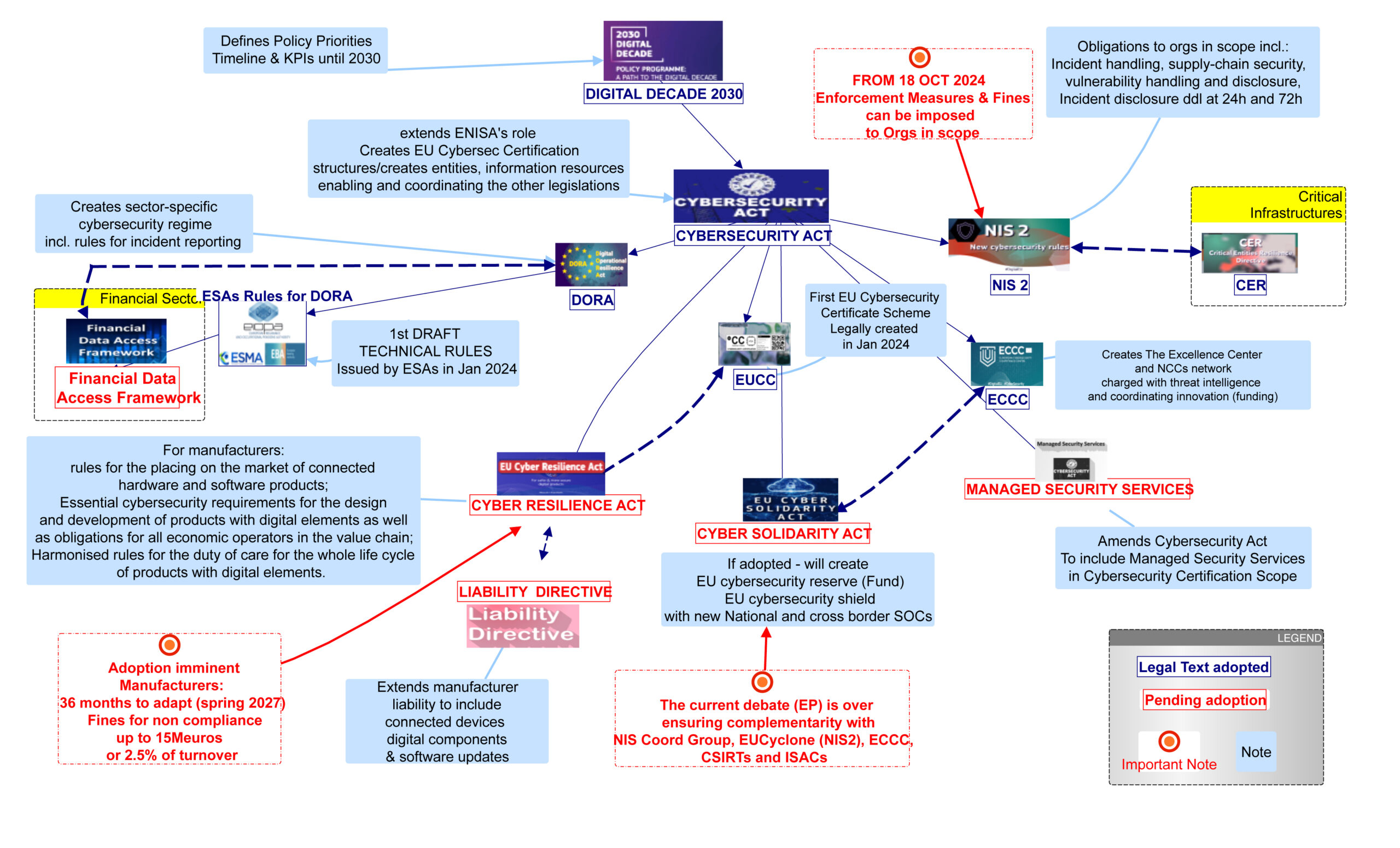

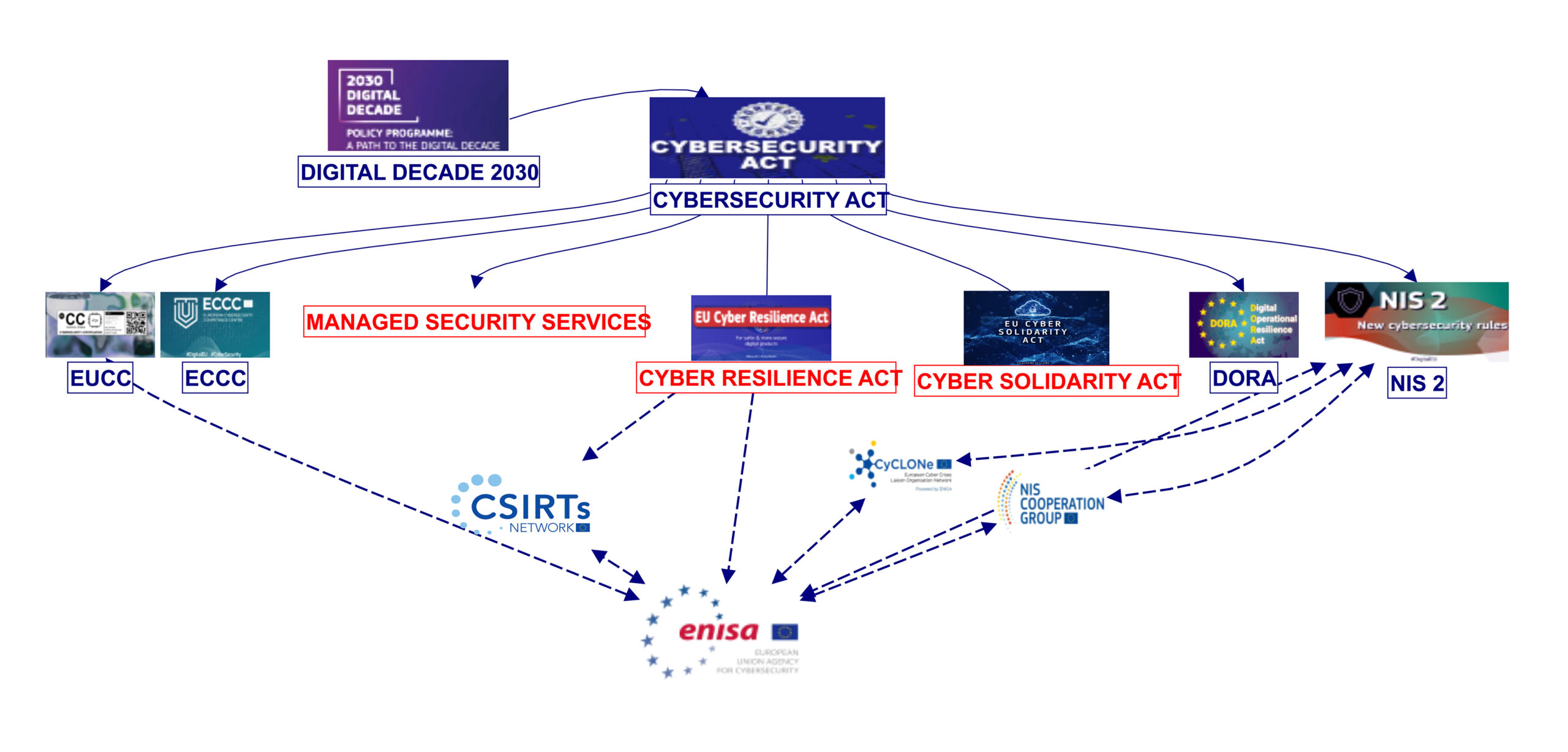

The wide-ranging cybersecurity legislation produced during the VDL commission is clearly aimed at providing this much needed new architecture. Among those key texts, several are still in the process of adoption, including the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) and the Cyber Solidarity Act. Among those already adopted are two other significant parts of this architecture: the Cybersecurity Act and the NIS2 directive.

The visual mapping below only shows how these texts relate to each other to form the regulatory architecture resulting from the VDL commission era. The majority of those rules will come into effect within the next 3 years. Their “real-world” impact will only be truly measurable around 2027.

In practice, the greatest and most direct effect for economic operators will come from two of those legal texts:NIS 2 which is to be transposed in national laws by the 17th Oct 2024, with penalties and fines theoretically possible from the 18th Oct 2024 and CRA which awaits the last formal step from the council as of the time of writing. The text of the CRA is final. Its key features have been largely discussed already. The changes introduced in this final version are worth discussing here. Notably because they affect the vulnerability reporting which will be the first part to take effect, 12 months after signature. We can expect those requirements to kick in around this time next year. That is, Spring 2025.

THE EP’s FINAL VERSION added items in the categories demanding stricter conformity assessment the explicit mention of “smart home products with security functionalities, such as smart door locks, baby monitoring systems and alarm systems, connected toys and personal wearable health technology”.

ON FREE AND OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE: The EP went to great length in the preamble to comprehensively address scenarios involving free and open source software in order to exclude the production, distribution, maintenance and sponsoring of free and open-source component and software from manufacturers responsibilities when no profit is gained and invites ad hoc decisions for ambiguous circumstances involving non-profit and for profit provision.

ON VULNERABILITY REPORTING: The final document contains new articles elaborating on the details of the process, effectively reinforcing the roles and responsibilities of CSIRTs and ENISA. CSIRTs are now at the front, as a primary reporting point, along with designated national authorities and cooperating closely with ENISA in the decision-making regarding what and when of the reported information will be made public. The matter of public announcement of vulnerabilities – as required in the original – has been the object of great debate with some suggesting it could backfire. Whether this proposed process will satisfy the critics is not yet clear. Article 16 is entirely dedicated to the central reporting platform for which ENISA will be responsible. The change, here, is structural. The original text mapped the reporting process to that of NIS2 which introduced “coordinated reporting”, placing designated national authorities as first point of call. In the original text, the platform made a peripheral appearance as an option for the reporting manufacturer to consider in addition. The final text specifies “A manufacturer shall notify any actively exploited vulnerability contained in the product with digital elements that it becomes aware of simultaneously to the CSIRT designated as coordinator, in accordance with paragraph 7 of this Article, and to ENISA. The manufacturer shall notify that actively exploited vulnerability via the single reporting platform established pursuant to Article 16.”. The 24h and 72 hours reporting deadlines apply.

Relation to NIS 2: Finally, another noticeable change in this latest version is the reference to NIS 2, added throughout the text, to clarify complementarities between both texts. For instance, Cloud Services already regulated through NIS 2 are, in principle, out of the scope of the CRA. But there is an exception when such service enables remote access necessary to operate the device. On the vulnerability reporting, ENISA decides but is no longer obligated to inform the NIS 2 group eCyclone of relevant incident and CSIRTs are introduced in the decision loop.

What this means for Businesses: between NIS 2 and the CRA, cybersecurity regulatory requirements will increase for mostbusinesses operating in the EU single market. In some sectors, this will mean all of them. Under NIS 2, organisations in-scope -which NIS2 broadens to new sectors – have the obligation to perform cybersecurity due-diligence on their own supply chains and service providers. Under the CRA, the entire business ecosystem around manufacturers, distributors and vendors of any product with digital connected component (both B2B and B2C) will be impacted. Whether they fall directly or indirectly under the scope of NIS 2 or the CRA, many business actors will have to evolve their cybersecurity practices from piecemeal and checkbox compliance to 360° awareness and risk management. Fines and penalties introduced in these and related laws, will make non-compliance too costly to contemplate. The question remaining for many is how to comply without facing prohibitively rising costs.

asvin’s Risk by Context: Building on its experience with the Automotive industry – a sector with a cybersecurity regime already so stringent, it was exempted from some of the above – asvin set out to develop the comprehensive answer to risk management,regulatory compliance and cost-control. This is what led to the development of our Risk by ContextTM approach.